Unwillingly, I wrote a book on gender violence. I did not want to, because my immediate motivation was not to deal with the subject, but to try to understand something that had surprised me, namely the absolute discordance between the vision of a woman who, to put it bluntly, I define as “strong” (independent, responsive, capable) and my imagination of a woman victim of violence. I believe that the word victim always leads us astray, because it contains a judgement, and induces us to imagine a fragile, submissive person. I too, therefore, am a victim of prejudice, intrigued by the obvious contrast between the stereotype of the abused woman I had in mind and the temperament manifested by Luciana Cristallo during the interview she gave to the journalist Franca Leosini for Italian public television. I began to enter the lives of the protagonists of the story, and tried to approach them without prejudice, to simply study the story of two human beings, he physically violent and she who suffers and is subjected to it. A woman who suffers and forgives. For twenty years.

When I started writing the book, I was certain that I would side with the woman. As I studied the thousands of pages of court documents, however, I seemed to intercept the motivations that drove Domenico (this is the husband’s name) to use violence on his wife. Obviously this does not in any way mean justifying his actions, I am simply accounting for a method and, perhaps, a more effective way of dealing with the issue of violence than judgement. That is to say, I have formed the idea that only by thoroughly investigating what moves the hands of men - of each man, in each particular and unrepeatable story - and what indirectly compels women to remain at their side, can we glimpse a solution to the production and reproduction of these dynamics.

Generally speaking, the feminist revolution, which was the only successful one in the 20th century, has borne its consequences and still manifests men who are unprepared for their female companions’ autonomy. Instead, they react violently to a freedom that they may pretend to accept superficially (to speak only of contemporary Western culture), and only then by navigating the currents of political correctness. If Political correctness is expressed through words alone, it is even dangerous. After all, if we had interviewed Domenico, we would have discovered that he had learned to answer that Luciana had an equal right to be free. Instead, in reality, he just did not think so. His hands, his whole body, did not think so.

Dealing with the psycho-physical combined in Dominic, there is a point in the book where I turn to those who had faced him, those who knew him, and ask them why no one stopped him, or helped him stop. The question obviously remains unanswered.

Unfortunately, this incident took place in the years when the female figure was still imbued with the sacrificial mode she had tolerated for centuries, mainly due to her economic dependence on her husband. In the Bruno household (the use of her husband’s surname to define the family unit is no coincidence here), from a certain moment onwards it is Luciana who maintains the family, but the entire socio-cultural structure of our country has not yet digested and made real the feminist impulse towards true, concrete, everyday, multiform equity. It has taken a long time for social and legislative achievements to become a reality experienced by everyone, in every far-reaching corner of every country. And Domenico - so the facts say - like so many men of his generation still thought of his wife’s body and her life as his own property. Domenico’s property, it urges and pains me to specify.

This is why I am convinced that places such as the C.A.M., Maltreating Men Listening Centres (a non-profit organisation founded in Florence in November 2009, which in 2014 opened other branches throughout the country) that are spreading throughout Italy are a strong impulse towards a more balanced future. In them, men are welcomed without judgement or prejudice, and find themselves placed in a condition to learn to understand themself and his own tensions and conflicts, before they result in acts of violence. We all contain evil and good, and to welcome the other, to know profoundly that the other has the same rights as us, is the result of a decision, first, and then of a daily exercise, it is the result of learning, because we would otherwise be led by the oldest part of our nature to attack those who threaten our borders or our property. So, as I write in the book, it is crucial to intercept the signals of encroachment of the controlled and civilized part of us into the reptilian, instinctive, aggressive part.

We must learn to recognise the moment when the primordial serpent uncoils within us. And stop it, before it takes control of us, drive it back into its own darkness and do something else with it. Maybe art, perhaps sport. Until we learn respect, slowly, one day after another, one year after another, eventually becoming biological, spontaneity, and habit. And one discovers, finally, the joy of it. The victory, that is, over the atrocious loneliness of those who control the lives of those they love. As a blind man. Without seeing them.

by Maria Grazia Calandrone

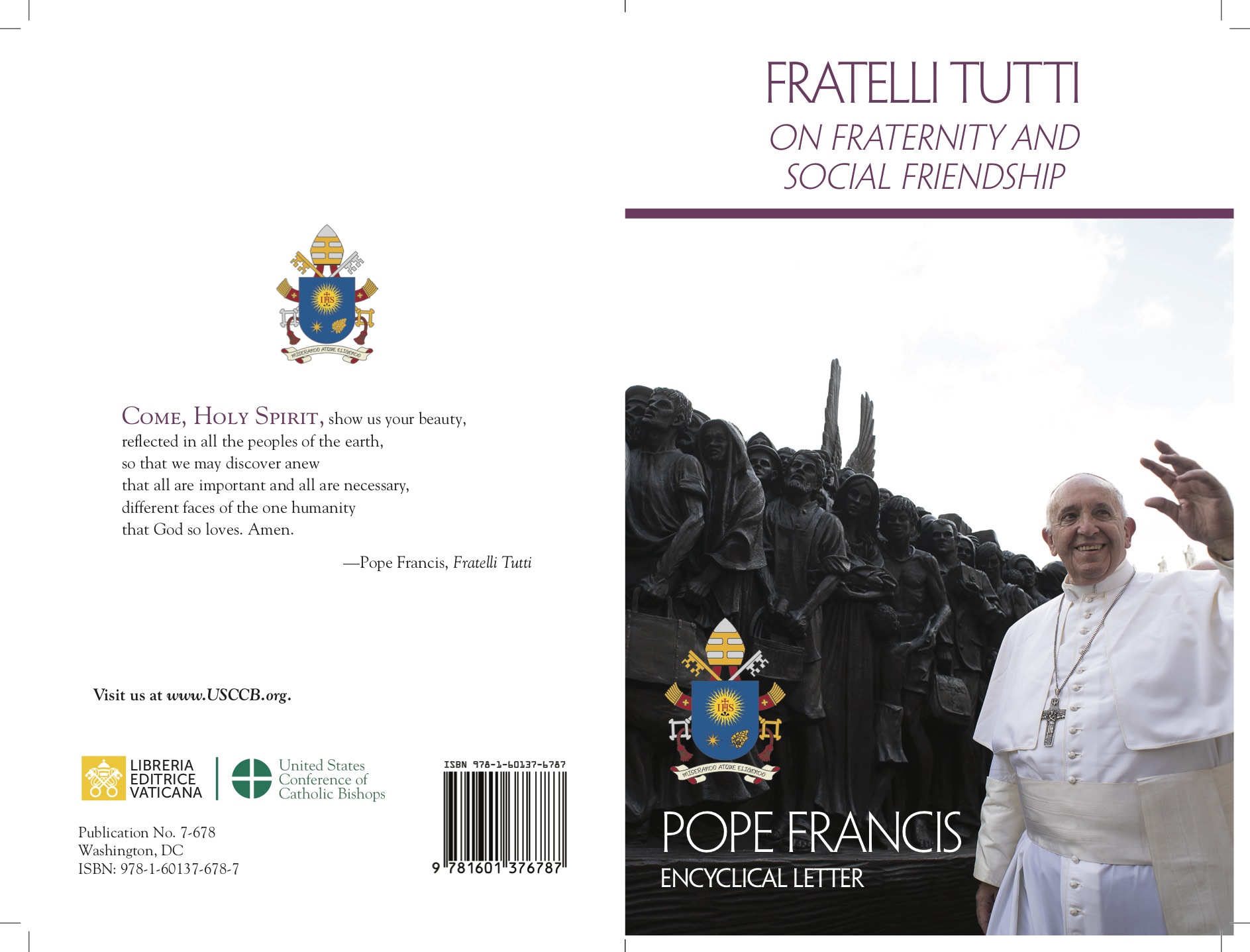

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti