Business manager Ajay Banga has been the President of the World Bank Group since June 2023. The financial organization, headquartered in Washington, d.c., was created in 1945 after the Bretton Woods Agreement, with the goal of combating poverty and providing aid to developing countries. In an interview with Vatican media before his recent visit to Rome, President Banga described the organization’s work to become a “better” and “faster” Bank in a complex and ever-changing international scenario.

“One of the first things we did”, affirmed Banga, “was to expand the vision of the Bank to include the intertwined challenges of fragility and conflict and violence and pandemics and climate, and realize that all that put together was a challenge on the fight to fight poverty”. The World Bank, said the President, is therefore racing against the clock to approve financed projects in the poorest countries. From an average of 19 months “to take a project from a conversation to approval by the board”, they are now “down to 16” and “looking to reach 12 by the middle of [2025]. In some cases”, explained the President, “we’re already much better. We recently approved five healthcare projects in five countries in Africa in less than 100 days. We have approved a correspondent banking project in the Pacific Islands in less than 10 months”. But it isn’t just a matter of speed. The President highlighted that the Bank has “made a lot of progress” in “working better in the institution and with partners”. He explained that the World Bank today works closely with the various multilateral development banks, such as the Inter-American Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the African Development Bank.

At the end of October, the World Bank concluded its annual meeting in Washington. One of the priorities that emerged was the creation of jobs for young people in developing countries. “There are 1.2 billion young people in the emerging markets who will become eligible for a job in the coming 10 or 15 years, and currently, the same countries are on the pathway to generate only about 420 million jobs. So this is a very big gap”, stressed Banga. Eight hundred million young people would be out of work. “If you want these young people to be a positive contributor to our world”, said the President, “you have to give them the dignity, the hope and the earning power of a job” in the broader challenge of “eradicating poverty on a liveable planet”.

“The World Bank Group”, he insisted, is “the one institution that has all the component parts to make it possible to get jobs generated”. That can be done through a combination of public and private sector parts at the disposal of the Bank in key sectors such as education, healthcare and infrastructure. “We finance, every year, somewhere between 60 and 70 to 80 billion dollars of projects in that space across the emerging world”, said Banga, explaining that the World Bank also does more than just financing. “It shares best practices and successes on how to do these things across countries”, which is why, he said, “we’ve set up these World Bank Knowledge Academies for bureaucrats and politicians in these countries to come and learn best practices from other countries”, and he added, “to get these governments to enact business friendly policies, regulations and policies so that small businesses, small farmers, big businesses, global businesses, feel that this country is a country, that they can predict the system and they can look to invest and hope to win based on the quality of their work, rather than have to deal with regulatory uncertainty”. He noted that “70 to 80 percent of jobs in every country, including in Italy and in the US and in China and in India, are generated by small- and medium-sized enterprises, and not by the government, but by the private sector”.

During the interview, the President of the World Bank then turned to Africa, focusing specifically on the five crucial sectors for job creation: infrastructure, agriculture, healthcare, tourism and manufacturing. “Africa is currently food-stressed, but it has land and it has water, but it doesn’t have irrigation”, he said. “If you grow food in Uganda and you want to move it to Angola”, he explained, “you have to send it on a ship to China to bring it back around the Cape of Good Hope, because they don’t have roads, railways…”. Another essential element for development in Africa is electricity. “Without electricity”, observed Banga, “nothing happens. Six hundred million people in Africa do not have access to power. We have committed with partners and the African Development Bank and charities like the Rockefeller Foundation to reach 300 million people by 2030”. As for primary healthcare, the World Bank has committed “to reach 1.5 billion people across the world” by 2030 — with a large part of those people in Africa. The World Bank also focuses significantly on agriculture. “We have just submitted at our recent annual meeting that we will double our funding for agriculture as a business to nine billion dollars a year to help develop small farmers and connect them to the supply chain of agriculture”.

President Banga then highlighted that the 78 poorest countries in the world will spend about half of their revenues on debt-related services, which is more than what they spend on healthcare, education and infrastructure. “We work with the imf on what’s called the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable”, he said. “The big change over the last 20 years is that the debt in the emerging markets is not just from Western countries” but also from bilateral lenders like China and India”, and from “commercial lenders”, he said. That’s why, he added, “the G20 created a common framework to deal with this, and four countries in Africa — Chad, Ethiopia, Ghana and Zambia — raised their hands to go through it and through this roundtable to try and find a way to reduce their debt burden. Zambia and Ghana have more or less completed their debt restructuring. Ethiopia is doing it and Chad is a little bit behind, and much needs to be done to make this process faster”.

The World Bank is the only institution to give money to these four African countries ever since they entered the G20 framework. “We have given them 16 billion dollars in the last four years, about half of that completely as a grant, meaning no repayment, no interest”. But the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund’s focus is on States with temporary liquidity problems due to the very high interest tax with which their debt is being re-evaluated, and, in general, on the poorest countries.

One resource used in these cases is aid granted by the International Development Association ( ida ), a World Bank entity which grants subsidies and loans at close-to-zero interest rates in exchange for agreed-upon reforms. “Seventy-eight countries”, he explained, “are currently recipients of money from ida ”, which is “very affordable financing”. Moreover, beneficiary countries receive the World Bank’s knowledge. For example, explained Banga, “we can take the best practices on digital public infrastructure from India and take it to 20 other countries”. Another element “is leverage, because we have a Triple-A rating as an institution. We can take every dollar given to us by our donors and multiply it through the private bond market by raising bonds at a very reasonable price for as much as three and a half to four dollars for every dollar. So it really means that if we raise 20 billion from donors, we are able to convert that to 80 to 100 billion of lending over three years”.

Over the years, 35 countries have gone from being beneficiaries of ida financing to being big donors. People forget, concluded Banga, that “South Korea was an ida recipient”, as were China, India and Türkiye. “So there is a success story in ida ”, he said, which testifies to the fact that these forms of aid are “the best deal in development”.

Valerio Palombaro

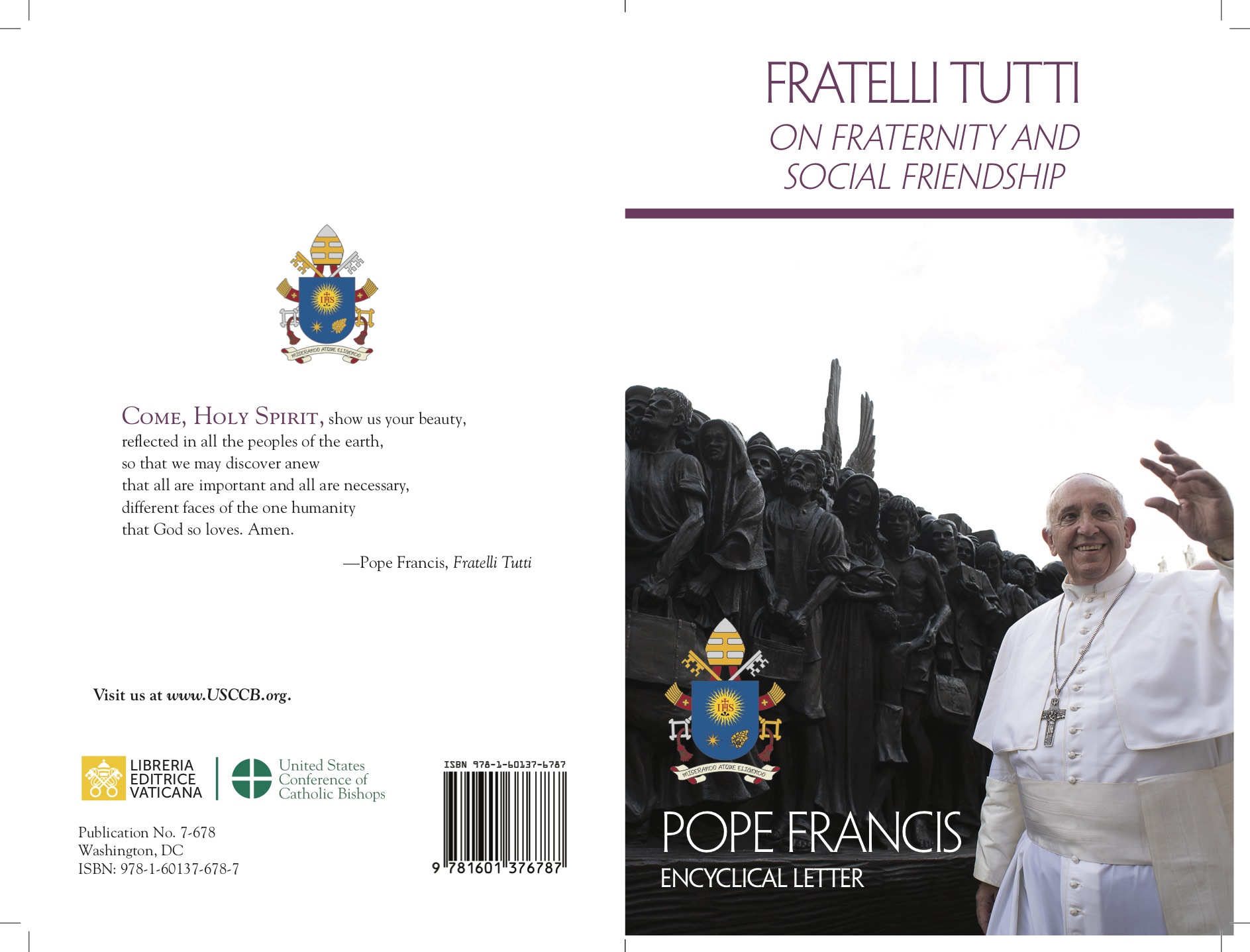

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti